Summer of Sleaze is 2014’s turbo-charged trash safari where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction and Grady Hendrix of The Great Stephen King Reread plunge into the bowels of vintage paperback horror fiction, unearthing treasures and trauma in equal measure.

Moonlight over a lonely town. Fog swirls. Whispering shadows. Footsteps in the forest. A voice from the darkness. A movement seen from the corner of the eye. A slowly spreading stain of red.

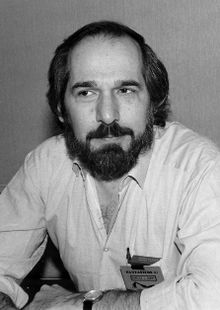

New Jersey-born writer and editor Charles L. Grant (1942–2006) championed these hallmarks of old-fashioned horror tales, even in spite of their simplicity, their overuse, indeed, their corniness, because he knew in the right hands such subtle details would build up to an overall mood of dis-ease and weirdness. Evoking fear of the unknown, not the graphic revelation of a psychopath with a gore-flecked axe or an unimaginable, insane Lovecraftian nightmare, is what a truly successful horror writer (or, for that matter, filmmaker) should do. And especially during the 1980s, when he published dozens of titles through Tor Books’ horror line, Grant did precisely that.

Grant was a prolific, well-respected, and award-winning horror novelist, short story writer, lecturer, and editor throughout the late 1970s until his death in 2006. He was perhaps the most vocal progenitor of what came to be known as “quiet horror.” In cinematic terms, Grant had more in common with the horror film classics of Val Lewton and Roman Polanski than he did with the writings of Stephen King or Clive Barker: suggestion, suggestion, suggestion.

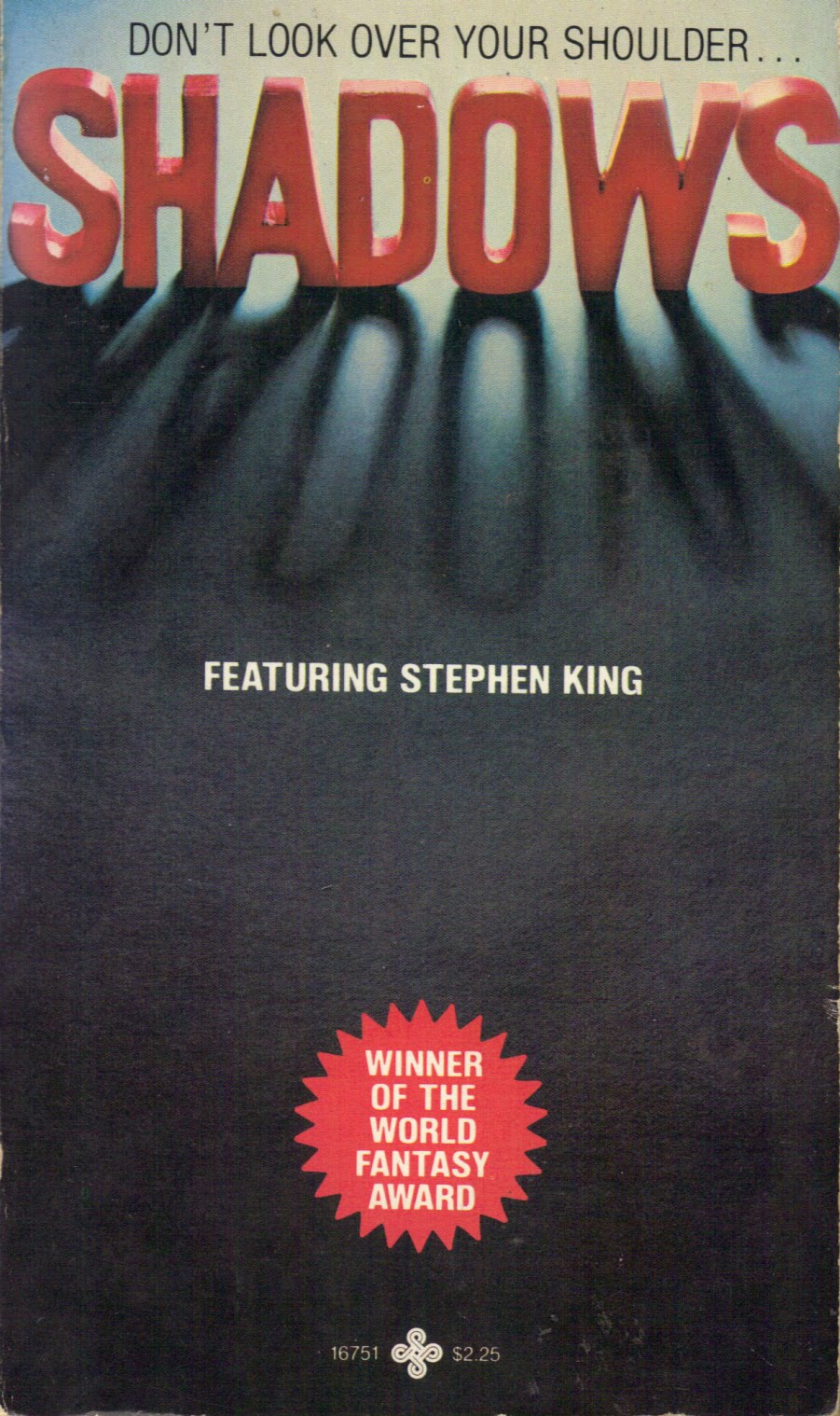

Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen, and Shirley Jackson were forebears, while Ramsey Campbell, T.E.D. Klein, and Dennis Etchison were fellow travelers in this sub-sub-genre, as were many of the writers to appear in Grant’s long-running horror anthology series entitled Shadows (1978—1991). These were tales, like Grant’s own, of subtle chills, crafted prose, and sometimes overly hushed climaxes that might leave readers looking for stronger stuff a bit perplexed. But when quiet horror worked (which was quite often) you felt a satisfactory bit of frisson knowing you were in the hands of a master teller of terror tales.

Like many horror writers of the ’70s and ’80s, Grant had grown up in the 1940s and ’50s and therefore was a great lover of the classic monster movies from Universal Studios, whose stars have become legend. The lesser-known works of producer Val Lewton also made a huge impression on Grant, and in an interview with Stanley Wiater in the book Dark Dreamers, he expressed his admiration for Lewton’s style of light and dark, sound and shadow, and only mere hints of madness and violence.

In 1981 Grant spoke with specialty publisher Donald M. Grant (no relation), ruefully noting that the classic monsters like Dracula, the Mummy, and the Wolfman had become objects of fun and affection (and breakfast cereal) rather than the figures of terror they had been intended. As a lark, the two Grants decided to produce new novels featuring the iconic creatures, although still in a 19th century setting.

They all take place in Grant’s own fictional Connecticut town of Oxrun Station—the setting for about a dozen of his novels and many of his short stories—these books “would be blatantly old-fashioned. No so-called new ground would be broken. No new insights. No new creatures,” according to Grant. Setting out to recreate the moonlit mood, graveyard ambience, and cinematic stylings of those old monster movies, Grant delivered three short (all around 150 pages) novels for those hardcore fans of black-and-white horror.

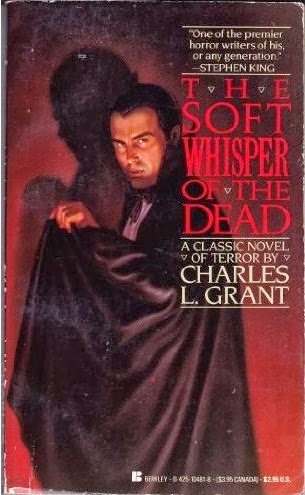

The first title, issued in hardcover in 1982, was The Soft Whisper of the Dead. Here you see the October 1987 Berkley paperback featuring a kinda-sorta Dracula (one presumes Universal wouldn’t allow the use of Lugosi’s image) in classic pose. In the intro Grant also expresses a fondness for Hammer horror, so I threw on a mix of James Bernard’s Dracula scores as I began reading. I recommend it!

Like lots of Hammer horrors, you get upper-crust polite society and regular folks and then the help, and does Count Brastov like the help! Pity the poor. Anyway he wants Oxrun Station all to himself, along with the help of Goth gal-pal Saundra Chambers, who can get him invited into all the best parties. Lots of description of weather and damp stone and a black wolf prowling about, some bloody fang-action, couple drained bodies turning up, lots of Brastov’s speaking imperiously and a chilly climax make Soft Whisper more a novel of “classic terror” than the other way ’round.

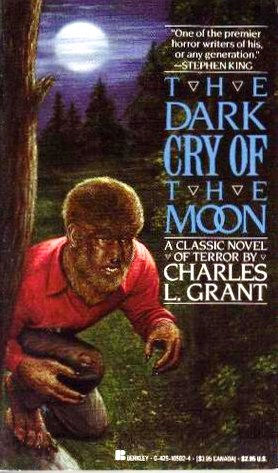

The next volume followed only a month or two later. Although we see Chaney’s Wolf Man about to pounce on the cover of The Dark Cry of the Moon, the werewolf that appears in the novel is actually a white-furred creature of much greater viciousness than we remember from the 1944 movie. I’m not a great fan of werewolf fiction (I prefer something like Whitley Strieber’s wonderful Wolfen) because the appeal of them lies in seeing the transformation. The emerging snout and sprouting hair and teeth becoming fangs simply don’t have the same gasp-inducing awe in cold print, but Grant does a brief bit of attempting it:

A baying while the figure began to writhe without moving, began to shimmer without reflecting, began to transform itself from shadow black to a deadly flat white. The baying, the howling, a frenzied call of demonic triumph.

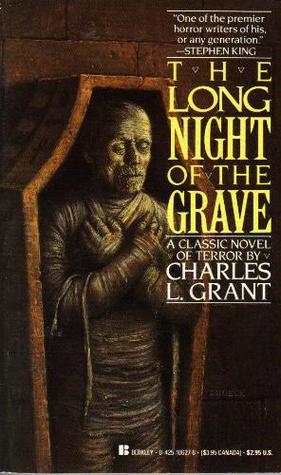

Last is The Long Dark Night of the Grave, and here we get the Mummy. Mummy fiction, huh, I dunno. The Mummy was never really all that scary, was he? Perhaps it’s his implacable sense of vengeance and not his speed that’s supposed to terrify; he won’t stop, not ever, like an undead Anton Chigurh, I suppose. There’s no reasoning, there’s nothing behind those shadowed sunken eye sockets (remember the ancient Egyptians took out the brain through the nasal cavity). This mummy goes after unscrupulous Oxrun Station fellows dealing in Egyptian artifacts, creeping up on them and then when they turn around he’s got ’em by the throat. Never saw it coming. Well, maybe a shadow and a scent of sawdust and spice…

Overall, these three novels are very light, minor entries in Grant’s Oxrun Station series; maybe imagine scary 1940s flicks never made. I think it’s obvious he wrote them more to satisfy his own nostalgia than anything else; his other fiction is more astute and focuses on modern fears than these simple, sincere, cobwebby tales. They certainly won’t appeal to readers who like their horror cheap and nasty.

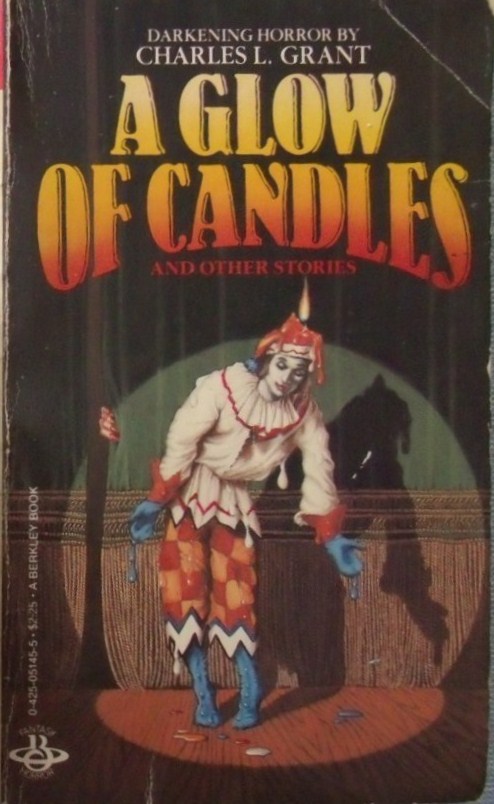

Those looking for Grant in top form would be best served by his Shadows anthologies and his own short fiction (collected in A Glow of Candles and Tales from the Nightside). While nicely written and offering some mild, Halloween-y spookiness and old-timey charm, Charles Grant’s Universal novels are probably more collectible for their cover art (artist unknown, alas) than for what’s between the covers.

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.